|

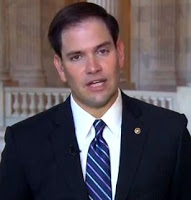

| Marco Rubio |

I'm stepping outside my main mission--raising awareness of animal issues--to remind us that abuse of animals, children, the elderly, or anything or anyone without a political voice, reflects on our humanity.

Twenty-two senators voted against the renewal of the Violence Against Women Act, including Rubio, the Republicans' golden boy. First, we should ask ourselves, what about protecting women, and others, needs re-authorization? Secondly, is to remember every one of these senators in 2014, and the 27 house Republicans.

John Barrasso (Wyo.), Roy Blunt (Mo.), John Boozman (Ark.), Tom Coburn (Okla.), John Cornyn (Texas), Ted Cruz (Texas), Mike Enzi (Wyo.), Lindsey Graham (S.C.), Chuck Grassley (Iowa), Orrin Hatch (Utah), James Inhofe (Okla.), Mike Johanns (Neb.), Ron Johnson (Wisc.), Mike Lee (Utah), Mitch McConnell (Ky.), Rand Paul (Ky.), Jim Risch (Idaho), Pat Roberts (Kansas), Marco Rubio (Fla.), Jeff Sessions (Ala.), John Thune (S.D.) and Tim Scott (S.C.).

Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and John Cornyn (R-TX) each attempted to tack amendments on to the Act that would annul the protections for undocumented immigrants, Native Americans and LGBTs. Each were voted down.

http://www.upworthy.com/taylor-swifts-new-song-about-feminism-is-pretty-catchy-and-blunt?c=upw1

Violence Against Women Act

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about United States federal law. For other related topics, see Outline of domestic violence.

United States federal law (Title IV, sec. 40001-40703 of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, H.R. 3355) signed as Pub.L. 103–322 by President Bill Clinton on September 13, 1994. The Act provides $1.6 billion toward investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women, imposes automatic and mandatory restitution on those convicted, and allows civil redress in cases prosecutors chose to leave unprosecuted. The Act also establishes the Office on Violence Against Women within the Department of Justice. Male victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking may also be covered.[1]VAWA was drafted by the office of Senator Joe Biden (D-DE), with support from a broad coalition of advocacy groups. The Act passed through Congress with bipartisan support in 1994, clearing the House by a vote of 235–195 and the Senate by a vote of 61–38, although the following year House Republicans attempted to cut the Act's funding.[2] In the 2000 Supreme Court case United States v. Morrison, a sharply divided Court struck down the VAWA provision allowing women the right to sue their attackers in federal court. By a 5–4 majority, the Court overturned the provision as an intrusion on states' rights.[3][4]

VAWA was reauthorized by Congress in 2000, and again in December 2005.[5] The Act's 2012 renewal was opposed by conservative Republicans, who objected to extending the Act's protections to same-sex couples and to provisions allowing battered illegal aliens to claim temporary visas.[6] In April 2012, the Senate voted to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act, and the House subsequently passed its own measure (omitting provisions of the Senate bill that would protect gay men, lesbians, American Indians living in reservations, and illegal aliens who were victims of domestic violence). Reconciliation of the two bills has been stymied by procedural measures, leaving the reauthorization in question.[7]

On January 2, 2013, the Senate's 2012 reauthorization of VAWA was not brought up for a vote in the House. While the bill was not reauthorized, its provisions (as enacted in the 2005 reauthorization) remain in effect.[why?]

On February 12, 2013, the Senate passed an extension of the Violence Against Women Act by a vote of 78-22.[8] On February 28, 2013, the House of Representatives passed the extension by a vote of 286-138, with unanimous Democratic support and 87 Republicans voting in the affirmative.[9]