THE FISHERMAN

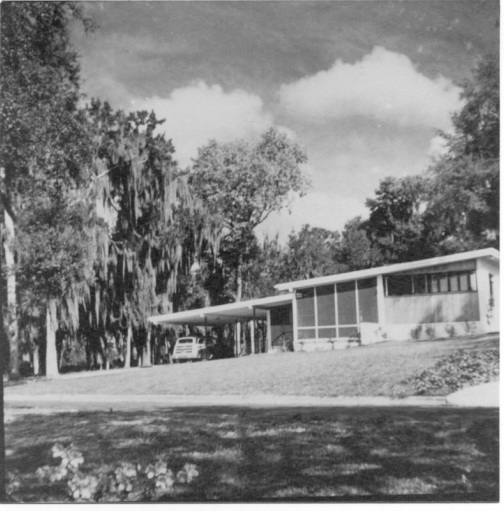

Daddy in the Big Cypress. That's a cypress knee.

“Noel was a far, far, far from perfect man,” says the minister at Daddy’s funeral. He is our next-door neighbor, so he knows. I lean my head close to Momma’s. “That was one ‘far’ too many.”

We have to laugh. Daddy would have.

My father had a massive stroke. In the twenty-three days it took his heart to stop, Momma, always a coward about being alone, moved herself out of their home on Lake Sue in Winter Park, and into a one bedroom apartment in a high-rise retirement complex in downtown Orlando. She bought it the day after the doctors said my father would not recover. It was where she wanted to be, where she had pressured Daddy to move as his health failed. My father resisted, calling places like my mother’s new home an outside cell at Sing-Sing. This from a man who spent the last five years of his life in a cinderblock bedroom with windows set too high in the wall for him to see the lake.

After the funeral, I drive Momma to her new apartment, and then return to spend my last night ever in our ugly little house on the lake. The house is dark and abandoned-looking, though it has only been empty for three weeks. I park on the slope of the driveway and get out, but find I’m not ready to light its shell. I cross the road to the lake. The still surface glitters with the reflections of lights from the houses now crowding the shore.

Daddy’s small aluminum fishing boat, with its faded camouflage paint job, has been pulled up onto the grass, flipped and chained to the oak tree. I sit on its stern, lie back, and look at the sky through the branches.

“Are you up there?” I ask aloud. Is there an up-there?

The headlights of an approaching car flicker across the trunks of the cypress trees along the minister’s share of the shoreline. When it reaches the curve before our house, it will have me fully in its sight. Inexplicably, I roll off the side of the boat to hide from the moment of exposure. After the car passes, I get up, brush the crushed oak leaves from the front of my funeral dress, and cross the road, ready, I think, to face the dark emptiness of our concrete house.

The living room furniture has been moved to my mother’s new apartment. Packed boxes line the walls, none of which hold Daddy’s things. My mother has left his room for me, and I’m glad. I want time to think about him, to search among his things for the man he was, our live-in enigma.

I spread my sleeping bag on Daddy’s bed, and take a bottle of wine from the sack of supplies I brought with me. All the glasses are packed, but I remember the stack of yogurt cups in Daddy’s bathroom. There are nineteen in a single column, more in the cabinet under the sink—Dannon—all flavors. I never thought to ask why he was saving them—the first of so many questions I have, now that it’s too late. I take a vanilla from the middle, rinse, and fill it to the brim with wine.

From the extra boxes flattened between the wall and Daddy’s bed, I select two tall ones, open and place them in front of his closet: one for Goodwill and the other destine for the dump. Four old and shiny Hickey Freeman suits hang on the pink, yarn-covered hangers I made for him thirty years ago. The first three I fold into the bottom of the Goodwill box, dropping each yarn hanger into the other. The last one is beige wool and still has the water stain around the jacket a couple of inches beneath the armpits, the padded shoulders are dusty and gray with age. I press it to my cheek and try to remember how strong his arms were when I was small.

The day he got the suit stained, I’d leaned our fishing poles against the carport wall and killed time waiting for him to come home from work by wading back and forth in the shallow water feeling for clams with my toes. I collected a half dozen before he pulled in, honked and waved. He had both poles and a bottle of beer in each pocket of his beige wool suit when he walked down to the lake.

This was before he built the dock, but he’d laid three two by fours side by side from the grass into the water to use as a boat ramp.

He opened one of the beers, took two huge gulps and put it back in his pocket. After he baited his hook and cast his line, I brought my hook in for him to bait with a piece of clam, then waded in up to my knees, trying to fling my bobber beyond his. He grinned, reeled in his line, stepped a foot or two out onto the two-by-four boat ramp and heaved his line past mine, a yard short of the lily pads where all the biggest fish hid. I waded to the hem of my shorts and cast overhand again as hard as I could. My bobber landed just beyond his.

“Ump.” He reeled in his line, brought his arm around, leaned back and hurled it with a grunt, following through with his body. His left foot slipped down the ramp, hit the algae growing at the water line, and shot out from under him. He landed sitting armpit deep in the water. Mud and beer foam billowed up around him. When I laughed, he hooked me behind the knee with his shoe and dropped me alongside him.

I fold this suit and put it in the Goodwill box because I can’t bear to throw away what he kept for thirty years.

His fishing hat dangles from a nail in the closet door. The sweatband is stained dark and the beige plaid material on the bill is torn. I pick at the tear like a cuticle snag.

The day Daddy tore his hat we were in the rowboat on the far side of our lobe of the lake. A storm was coming, and the wind had picked up and blew straight at us. Between the wind and the way sound carries over water, we both heard the screen door slam and looked up to see Momma rush down the front porch steps. She waved her arms above her head, and pointed to the black sky to the west.

“Does she think I don’t see it?” He’d been trying to get us back, pulling hard on the oars, but the best he’d managed was the center of the lake. Between the rolls of thunder, when I kept my ears plugged, he smiled and talked about the bass we’d caught. Every time he rested, the wind blew us back toward the far shore.

“I think the smart thing to do is to follow the shore home instead of trying to go straight across. What do you think?”

His words were caught by the wind an instant before a jagged cut of lightning knifed into a grove of trees, splitting off a limb, which sizzled when the burning end hit the water. Thunder exploded a moment later, and I screamed.

The wall of rain chased Momma onto the porch, left the shore and moved across the water towards us.

“Here she comes.” Daddy grinned with his teeth clamped.

I whimpered.

“We’re gonna get a little wet, that’s all. And if you can squeeze up under there…” he meant the bow, “…only one of us will take a bath.”

He leaned aside to let me cross his bench and crawl up into the small, dry, cobwebby space. He took his shirt off and covered my goose-pimply legs.

When the rain hit, Daddy pulled his cap low against it. The long, orange rubber worm he had hooked to the bill slipped down to dangle off the left side and flick in the wind. Rain dripped off its tail. I watched Daddy’s brown back, wet and slick, strain to pull the oars, the cords in his neck appearing and disappearing with each stroke.

“You okay?” he called over his shoulder, and turned to let me see him smile.

His shirt had soaked through, and I shivered beneath it. “Yes, sir.”

“Good girl.” He turned back to fighting the wind, let go of an oar long enough to rip the rubber worm loose from his cap, and throw it down, where it floated and moved in the water around his feet.

I put his fishing hat in the box for the trash, but I’m grateful for the memory of when I thought my dad was a perfect man.

I take his pants off their hangers, fold and put them in the box with his suits. I sort his shirts, dividing them by their condition between the two boxes, all except one, the green wool plaid, XL. It reminds me of rubber waders hanging from a nail in the storeroom, his shotgun in the corner of his closet, and a kitchen sink piled high with dead ducks, smelling like wet pillows. I bury my nose in the wool and believe I smell the smoke from campfires, gunpowder, sweat and beer—traces of him. I put it on and roll up the sleeves.

When this house was built in 1951, the architect designed shallow, built-in closets in one wall of each of the three small bedrooms. Drawers, in double rows of three, are beneath the clothes rod. The top drawer on the right holds his socks and underwear. I empty it onto the bed to sort through, only to scrape the entire contents into box for the dump. The next drawer down is full of old Consumer Reports and American Rifleman magazines. Under the magazines are our targets from the gun range, my shots circled in red crayon, his in green. Every few months, when I came for a visit, it was my routine to lunch and shop with my mother on the first day and go target shooting with my father the next, dividing my time between two people who had nothing in common but me, my sister, and forty some odd years of a mostly miserable marriage.

The top drawer on the left was where he kept his wallet, which is empty, and the abalone shell that holds one cufflink, a nail file, three nickels and a penny. Next to the abalone shell is the rubber mallet he used to adjust the television when he was drunk and the picture rolled.

When I left home in 1964, we still had only two TVs, one in the back bedroom, my mother’s room, to which she retreated after she fed my sister and me, and the set on the back porch. If I wanted to watch something, it was a choice of sitting on Momma’s dressing table stool beside her bed and scratching her feet, or sit downstairs with Daddy, who talked through every program until he was too drunk to move his lips.

I remember how angry I’d get trying to watch a show with him droning on and on. The drunker he got, the ruder my responses until one night he stopped and turned to me with eyes full of concern. “Don’t you feel well, honey?”

I looked at my father and finally saw the lonely old man trying to talk to someone he loved who wasn’t listening. “No I don’t, Daddy. I’m sorry.”

There is a small, two-step ladder my father put at the foot of his bed so Shanty, our arthritic dog, could climb up to sleep beside him. I move it over to his closet.

His new 19” TV is in one corner of the top shelf. Its back end is resting on a broom handle, which tilts it forward enough for him to watch from bed. I unplug it, lift it off, and put it on the floor.

Sharing the shelf with the TV are old National Geographics, some of which have SAVE FOR GINNY printed in bold black ink. The article he thought would interest me is also circled in black. Beneath these are his records for the blind, which he needed after cataract surgery. A few of these also have SAVE FOR GINNY printed on them, though in a shakier hand.

There’s a folder full of warranties for appliances long gone and a 1963 calendar with his retirement date circled: February 23rd, the day after he turned sixty-two. Inside a scarred brown leather briefcase are a series of expense logs, 1949 to 1952, and a cracked, black leather holder with three yellowed business cards:

MOORE BUSINESS FORMS

Noel Rorby / District Manager

In a pocket in the lid is a thick, gold-rimmed sheet of paper that reads: “Salesman of the Year –1958 –in Appreciation.” With the award, sealed in clear plastic, are two dyed maple leaves, one red, one yellow, a checkbook from his cypress-knee lamp making business with five blank checks, and a register with a zero balance as of May 29, 1954.

I remember Daddy being a salesman all his life and had forgotten when, against my mother’s wishes, he took a chance, and risked us all for the dream of having a business of his own. He quit his sales job and opened a little factory where he made lamps out of cypress knees and dyed leaves fall colors for department store window displays. The business we called “the knees factory” failed after a year or two.

I put one of his business cards, his award, and the leaves back in the briefcase and put it with the TV.

Even though the night is warm, I keep his plaid shirt on, top off my yogurt cup with wine, and go back down to the lake. There are fewer lights now; people have gone to bed, leaving the lake looking darker, more like it did all those years ago.

I sit on the overturned boat and try to conjure our past, try to remember my father before he got compressed beneath the layers of his disappointments into the alcoholic old man who, until tonight, left only a bitter trace in my life.

The last thing I found, before returning to the lake, was Daddy’s stormoguide behind the Venetian blinds on the windowsill above his bed. I added it to the things I want to keep: his shirt, the abalone shell, the dyed leaves from the knees factory, and one of his business cards.

The stormoguide provides the temperature, humidity and a sense of the weather to come with its rising or falling barometric pressure gauge. I want it to remind me that, though Daddy loved Florida and living here, he hated the heat and suffered from it until the last years of his life when he couldn’t get warm. It occurred to me, as I put the things I would keep in his briefcase, that Daddy tracked his life in larger blocks of time than the rest of us do—by seasons. What I can’t decide, even now, sitting on the stern of his little boat, is whether he was trying to slow time down to catch up with his fleeting dreams or speed it up to out-distance the ghosts of his failures. I lie back, imagine my father, his shirt off to feel the sun warm on his shoulders, and I see him reel in his untouched bait and cast it out again.

Ginny's Novels